Behind the scenes at your local museum, curators, researchers, and historians make fascinating discoveries that deepen our understanding of our world’s greatest cultural treasures. This research sometimes gets published in scholarly monographs, exhibition catalogues, or presented in academic seminars. Unfortunately, the majority of all this valuable knowledge rarely trickles down to the average museum visitor or enthusiast. If you dig deeply enough, you might uncover a scholarly work in PDF form linked somewhere in the deep recesses of the museum’s website. But rarely is this information presented effectively as website content.

That’s too bad because the web is one of the best formats for the display of scholarly content. Too soon we forget that the hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP) and the hypertext markup language (HTML) were originally developed and deployed for academic use. The first draft of the world wide web was focused on expanding and improving access to academic content across institutions. Somehow, we went from indexing academic content to animating GIFs overnight.

But the invention of HTTP and HTML were, and are, perfect formats for scholarly information. Reading scholarly essays and monographs involves interacting with lots of references and footnotes. While these frequent references can interrupt the flow of normal reading, that scholarly apparatus does enable academic research to thrive. Sometimes one key observation in a footnote can set a scholar or researcher off in a new direction leading to deeper insight and new theses. In print, following threads in references and footnotes can be very inconvenient. But with HTTP and HTML embedded footnotes, hyperlinked references make following these details a researcher’s paradise. Making connections, deepening ideas, enriching sources — it’s all pure scholarship gold. And this is what the protocols and underlying web technology were meant to foster in the first place.

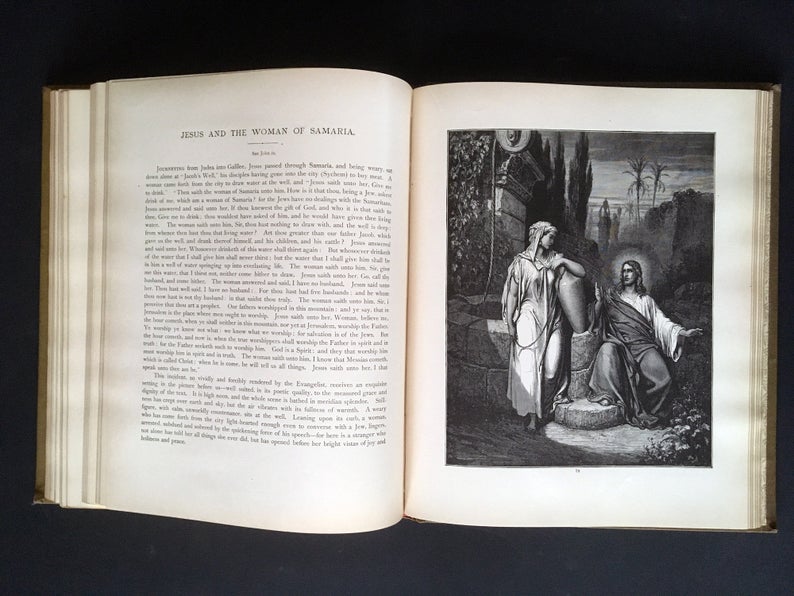

Additionally, in print form, research and scholarship have to be limited in scope. Museum catalogues are already expensive and physically heavy. Research has to be edited and limited to only the essential information. Much of the technical detail and supporting imagery has to be left on the cutting room floor. Online, space is unlimited. And any amount of desired detail can be added to academic content – not to mention the potential for video, audio, and other kinds of interactivity that a digital environment offers.

It’s ironic then, that the content that is most suited to this format is that which is either ignored or relegated to PDFs of printed versions of research.

This month, I’ll be showcasing a few examples of excellent web presentation of scholarly museum research. We’ll also look at a couple of relatively recent developments in web-based scholarly tools that can bring the treasures of research out into public view, and for other scholars to further benefit from your collection.

We’ll also learn from a couple of museum and art collection professionals who are involved with the coordinating and presenting of scholarly research: Alexa McCarthy, Curatorial and Collections Associate at The Leiden Collection, and Jennifer Henel, Digital Humanities Developer at the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art and digital art historian.

Web-based Scholarly Apparatus

There are a number of ways that web-based presentation is ideal for scholarly work. A few basic ones include tooltips for inline access to references and footnotes, embedded references to figures, and tabbed presentation of related information. A more advanced scholarly option is the use of IIIF manifests that allow for scholarly analysis and annotations using tools like Mirador. There are a couple of other concerns unique to web-based scholarly content, namely permalinks to the content for academic referencing of the content’s URL, and the implementation of high-zoom image exploration. Let’s take a look at examples of each of these.

The Basics – Online References and Figures

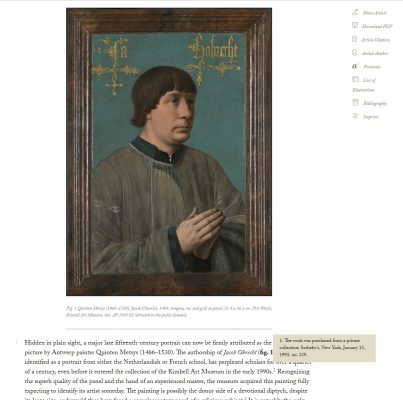

When it comes to scholarly content, in print or on the web, the multiplication of figures, references, and footnotes are part and parcel of academic work. But on the web, unlike in print, these references can benefit from inline tooltips that present the reference, footnote, or citation by simply hovering over a link. A great example of this is the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art. In their latest issue is an article about a new early painting attributed to Quinten Metsys . This article about a portrait of composer Jacob Obrecht has footnote references throughout the text, but unlike print references, these footnotes are links which, upon hovering over them, reveal the references floating above the text. No need to scroll down the page, or link down and then link back up. Also of note in JHNA articles is the numbering of each paragraph for each reference for commentary or discussion. In the case of the JHNA article, illustrative figures are presented above or below the paragraphs where they are referenced. This is much easier to do on a long-form webpage than in print. Usually, either due to page breaks, or the costs of color printing, print articles typically group up illustrations and figures rather than printing them inline with their textual references.

. This article about a portrait of composer Jacob Obrecht has footnote references throughout the text, but unlike print references, these footnotes are links which, upon hovering over them, reveal the references floating above the text. No need to scroll down the page, or link down and then link back up. Also of note in JHNA articles is the numbering of each paragraph for each reference for commentary or discussion. In the case of the JHNA article, illustrative figures are presented above or below the paragraphs where they are referenced. This is much easier to do on a long-form webpage than in print. Usually, either due to page breaks, or the costs of color printing, print articles typically group up illustrations and figures rather than printing them inline with their textual references.

Jennifer Henel helpfully points out that one very important aspect of handling citations and figures online is the need to include full reference information for every instance. In print, where all the references are grouped together, the use of “ibid.” in a footnote is clearly connected to the full reference that precedes it. But since online references can be accessed individually, without such context, an isolated “ibid.”would have no referent. So unlike print, fully articulated citations need to be included in each and every instance of online scholarly content.

Another example of inline references is our client The Leiden Collection. Looking at The Card Players by Jan Lievens, you’ll find similar inline references. But The Leiden Collection improves on this kind of implementation in a few ways. Footnote references display the reference inline upon clicking rather than on hover. It’s a small difference, but it preserves the functionality for mobile viewing, a context that doesn’t handle hovers effectively. Additionally, the figures, which run sequentially along the right hand of the page, are also revealed inline upon clicking. This opens up the extra visual information at the point of interest, when desired, rather than having to refer to elsewhere on the page. Another feature of The Leiden Collection’s implementation is the integration of glossary terms. When hovering over terms like “Chiaroscuro,” a definition is provided on hover (and linked to a glossary page with the definition).

Extended Related Content

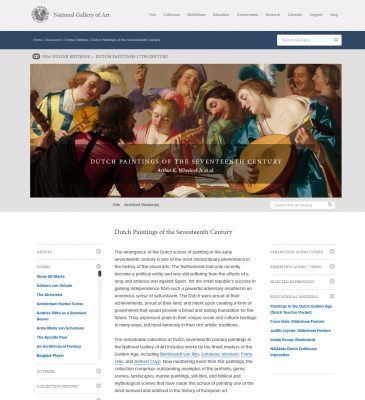

Another feature of scholarly content is its extended notes and related content. For example, a scholarly article about a particular work of art would have extended information about its provenance, its exhibition history, further background on the artist, and in-depth technical information. Rather than burying related content in appendices or notes at the back of a book, all of this related information can be provided in a tabbed or accordion interface. The National Gallery of Art provides robust related information among assorted accordion tabs in the right and left margins of the page. See their online addition of 17th Century Dutch Paintings. They have additional information about the artists, works, authors, collection history, exhibitions, collection and exhibition media, and educational material. Similarly, The Leiden Collection provides extended information but in a horizontal tab interface.

Another feature of scholarly content is its extended notes and related content. For example, a scholarly article about a particular work of art would have extended information about its provenance, its exhibition history, further background on the artist, and in-depth technical information. Rather than burying related content in appendices or notes at the back of a book, all of this related information can be provided in a tabbed or accordion interface. The National Gallery of Art provides robust related information among assorted accordion tabs in the right and left margins of the page. See their online addition of 17th Century Dutch Paintings. They have additional information about the artists, works, authors, collection history, exhibitions, collection and exhibition media, and educational material. Similarly, The Leiden Collection provides extended information but in a horizontal tab interface.

The Accelerating Pace of Scholarship

Alexa McCarthy notes that in today’s world of connected content, academics have more information than ever at their disposal as they pursue their research. And as historical archives digitize more and more of their warehouses full of photos and historical documents resources for research are more available than ever. Thus new discoveries and deep analysis are happening at an increasing rate.

But this also means that scholarship, printed in exhibition catalogues, has a shorter shelf life than ever. Reproducing updated versions of these hefty works is logistically and financially prohibitive. But in the digital context, revising and adding in new scholarly insights is simple enough, which presents an interesting dilemma. How does a scholar cite web-based scholarship when it’s quite likely that a scholarly article very well may change significantly over time? Jennifer Henel, in her work on the National Gallery of Art’s Dutch Painting of the Seventeenth Century project has learned that if scholars can’t trust the permanence of a source, they simply will not cite it.

With perhaps the exception of very minor copy-edits, it’s critically important that scholarly content maintain permanent access to every version of their online content, whenever additional information is added. What’s more, it should be adopted as a best practice that whenever a new version of a scholarly article is released, that the article maintains a version history as a part of its extended information. Just as you’ll often find a tab for Provenance, there should also be a tab containing an archive containing the article’s version history. Version history would be even more effective if it included a brief document giving a summary of the change history from one version to another. This simple practice would help maintain confidence in the coherence of online scholarship, even as it grows and changes over time.

The Problem of Peer Review

Jennifer Henel also points out that, with respect to evolving scholarship online, the issue of peer review can present problems. If an article undergoes revision after it’s been peer reviewed, the confidence that the original peer review gave is eroded. And it’s impractical to have every change or revision sent out for peer review. Again, maintaining the practice of not only keeping permanent access to past versions available, and documenting the version history, it would also be prudent to indicate which version in a version history was the latest to undergo peer review. That practice would allow scholars to have the confidence to include and integrate online scholarship into their own research and publishing.

Permanent Citation References

One last technical detail to consider when it comes to citations and changes that occur in the online context is the potential for URL and domain name changes over time. This can create a serious problem for archival access to scholarly references in web-based content. Care should be taken to preserve the complete URL structure that you include in official citations. If you ever change your domain name or adjust your URL structure, which often happens in a redesign project, you’ll need to be sure to set up 301 redirects so that old URLs map to their new locations. Alternatively, and perhaps preferably, you can utilize the services of the Internet Archives PURL project. By signing up for this program you can manage all your URLs and any changes that may occur on a platform designed to offer a permanent home for archival URLs.

Beyond the Basics, IIIF (“Triple-Eye-Eff”)

One of the most interesting recent developments in web-based scholarly apparatus of online artwork is IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework ) standards and protocols. Without diving into the deep-end of technical explanation of IIIF, but to give you an idea of its benefits, you need to first understand that there are two primary distinct aspects to IIIF: a presentation function, and an image display function (there are two newer aspects of IIIF relating to authentication and search, but we won’t be reviewing those aspects here). The overarching concept behind the IIIF initiative is the standardization of artwork data and image data in a way that can enable the sharing and comparing of this data across institutions. The presentation function requires the creation of a “manifest” formatted according to the IIIF standards, such that an object’s metadata (artist, genre, size, date, etc.) and other associations (other objects in its series like a sequence of pages from a book or manuscript) can be made available to other scholars and utilized in advanced scholarly tools such as Project Mirador. When the URL of an object’s manifest is accessed via Mirador the image and its information is loaded up and can be analyzed, inspected, annotated, compared, and shared with other scholars. Here’s a quick sample of some “scholarly work” I did on painted noses using the IIIF link provided by The Leiden Collection’s painting, The Card Players, with a self-portrait by Van Gogh.

) standards and protocols. Without diving into the deep-end of technical explanation of IIIF, but to give you an idea of its benefits, you need to first understand that there are two primary distinct aspects to IIIF: a presentation function, and an image display function (there are two newer aspects of IIIF relating to authentication and search, but we won’t be reviewing those aspects here). The overarching concept behind the IIIF initiative is the standardization of artwork data and image data in a way that can enable the sharing and comparing of this data across institutions. The presentation function requires the creation of a “manifest” formatted according to the IIIF standards, such that an object’s metadata (artist, genre, size, date, etc.) and other associations (other objects in its series like a sequence of pages from a book or manuscript) can be made available to other scholars and utilized in advanced scholarly tools such as Project Mirador. When the URL of an object’s manifest is accessed via Mirador the image and its information is loaded up and can be analyzed, inspected, annotated, compared, and shared with other scholars. Here’s a quick sample of some “scholarly work” I did on painted noses using the IIIF link provided by The Leiden Collection’s painting, The Card Players, with a self-portrait by Van Gogh.

IIIF and Deep Zoom Scholarship

One of the aspects illustrated in this silly example is that in both cases the image has been zoomed in to a particular detail of each painting. One of the compelling features of IIIF is that its schema can not only reference an image file, but it can maintain a specific state of a deep zoom (DZI tiling) image both at its level of zoom and its cropping. So scholars can reference not just an image, but precise details with an image. (For more information about deep zoom images see our recent blog post, A Case Study of Deep Zoom with OpenSeadragon). It’s a lot of fun to explore the details of paintings with a deep zoom viewer like OpenSeadragon, but for scholars working with detailed artworks and doing comparative analyses, the importance of IIIF image protocol is serious business. Particularly among scholars working with ancient manuscripts. The ability to zoom in on text, run comparisons, and get the observations of fellow experts in other institutions is a real boon to manuscript scholars.

The Getty Foundation’s OSCI Initiative

The Leiden Collection, The National Gallery of Art and the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art are certainly not the only collections engaging in the web-based presentation of scholarly content. In fact, in 2009 The Getty Foundation launched the Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative. This initiative exists to help museums make the transition from printed volumes to multimedia and web-based publications. This website links to many resources, reports, and examples of online scholarly museum content.

Going the Extra Mile with Scholarly Content

Of course, the real work behind scholarly content is the research and writing of the content in the first place. A research project can span months or even years and involve multiple staff. But this kind of work is an essential aspect of a collection’s mission. It’s already happening behind the scenes at your museum.

It does take some extra work to prepare and present that content online, and you may need some specialized website tools to maximize the implementation of web-based scholarly content. But according to Alexa McCarthy, “with the right sets of tools, the actual work involved to get that scholarship presented online can be as little a day or two. Of course, it’s not only about having the right set of tools, but also the structure in place within one’s institution that enables scholarship to be presented online in an efficient and timely manner.”

Considering how much time is invested in scholarly research, and how important that work is to your mission, doesn’t it deserve to published online, and not just in print? Isn’t it worth a day or two to give that work a digital platform? The value of your scholarship is a major resource of your institution, and the web is the best possible outlet for this work. So take the time to develop the tools, integrate the workflows, and publish scholarly work online. The academic world will thank you, and the broader world may learn even more about the importance and impact of your collection.