One of the persistent challenges of museum website design and content strategy stems from the vast quantity of content that museums have to manage. A museum website has basic information like their hours, ticketing, events, and institutional background, but it also produces so much more: educational content, scholarly content, digital stories, and presentations. Not to mention the core collection itself. There is so much diverse content that trying to organize it all under one navigation system can become a real puzzler. And the puzzle can quickly become a wrestling match when each department in the museum, with their various perspectives and priorities, vie for position and prominence for their content’s representation on the site.

So this month we’ll tackle the important topic of how to organize and represent museum content on a website, and address some important fundamental concepts of information architecture in general. And since we here at Cuberis spend just about every day either working on museum websites or evaluating others, we’ll add our experience and observations about trends that work, and some that don’t when it comes to labeling conventions in museum navigation systems.

But be forewarned, designing a simple information system is no simple task. In order to produce clear and functional website wayfinding systems, it will be very helpful to get a primer on some technical terms and concepts from information science. There are some formal rules to this terminology that we need to keep in mind when building something as basic as a navigation bar. So we’re going to spend some time on these concepts and rules. But before diving into terms like “genus and species,” and “extension” versus “intension,” keep in mind that there will always be exceptions to some of these rules. But we recommend striving to hold these rules as consistently as possible; only breaking them when absolutely necessary.

One other note before diving in, this article is a bit longer than most, due to the primer on terms and concepts. We need to cover that ground before we can apply them to the anatomy of a typical museum website. But if you’re curious about the upshot, feel free to scroll to the end, and then come back and work through the concepts that lead to our conclusions.

UX is for the Users

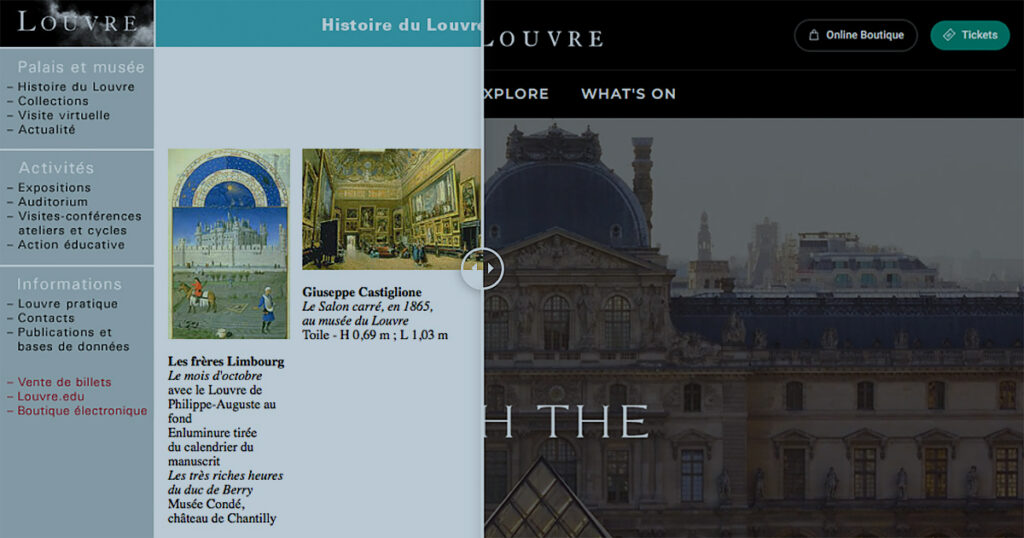

The first principle when it comes to user experience is that the function of a navigation system is for the user, not for internal staff or departments. This is an obvious and simple principle, but in practice, it’s really very hard to step away from viewing your website through the lens of familiarity with your internal organizational structures. We rarely recognize our native assumptions and insider perspectives and how they significantly influence how we read our own labels. For example, two commonly found main labels on museum websites are “Learn” and “Explore.” By “Learn” we usually assume it will include information about educational resources or programs. And by “Explore” it usually means, well frankly, ‘all the stuff we couldn’t find a place for in the other main sections.’ But from the perspective of someone who does not look at museum websites every day, would not these two labels have a significant overlap in meaning? What would a new visitor expect to find under those labels? What makes perfect sense to you and me, being familiar with the inner workings of museums, may be quite murky to a new visitor.

Information Science Terminology

Besides the basic need to step out from your internal org chart perspective, there are a few other principles from the discipline of information science that can help to evaluate your website’s organizational structures. These principles have historically been taught in the context of formal logic, so if it’s been a while since your high school logic class we’ll need to dust those topics off and re-master these skills.

The Attributes of Terminology as a Science

When building a website navigation system we not only need to establish categories, but we need to come up with fitting labels for each category. And for labels to function properly they need to have clear definition. But words can be tricky things. Words without context can become vague and ambiguous.

For example, what’s a record? If I created a website with just one menu item called “Records,” what would you expect to find? Public records like birth certificates and titles of deed? World records like, “most spoons balanced on a human body?” An ecommerce site where you can find some new vinyl albums? The fundamental meaning of some words without context can be completely ambiguous.

But even if we avoid ambiguous terms, we can also have label problems due to the vagueness or broadness of a term. For example, let’s consider the commonly used label on most museum websites, “Events.” The word “events,” by itself, without context, can refer to any number of occurrences. It could reference a sporting event, an historical event, a corporate meeting, or a show. Many distinct kinds of events can fall under its umbrella meaning. And the broader a term’s meaning, the more vague it becomes.

Now, in the context of a museum website, the word “events” is easily understood as a calendar of upcoming activities. But when you drop into a museum’s calendar page you’ll often find further classifications of event types: current exhibitions (as well as past and upcoming ones), openings, lectures, classes, films, fundraisers, and galas, for example.

Since the word “event” is necessarily broad, in order to sufficiently cover all the ground of event types, we need more filters and subcategories when we use an event list. There is a set of important hierarchical relationships between the term “event,” and those subcategories under it. Technically, the levels of these hierarchies, in formal logic, are called “genus” and “species.” Not to be confused with the terms “genus” and “species” as used in biology (though those biological relationships are similarly structured). As you move down from one hierarchy level to another (e.g., from “event” to “class”) you move from a genus term to a species of that term. And if you further divide a species into subcategories, the species becomes the genus of the species beneath it.

So a “class” is a species of the genus “event.” Likewise, “art class,” would be a species of “class” and “class” becomes the genus of “art class.” And we can observe a very helpful dynamic which occurs when we move up and down a genus and species chart. We see an increase of extension the higher we go and an increase of intension as we dig down into species and subspecies.

Measuring the Extension and Intension of Your Labels

The extension of a term is how broadly it can encompass other species. Conversely, the intension of a term differentiates one species from another and limits its scope by adding particular attributes that distinguish one species from another. So the higher up the genus chart we go, the greater the extension a term must have. And as we go back down the species chart the greater each term’s intension must be.

We identified a handful of event types that might be found under the genus “event.” And we could add more species under the term “class” besides “art class.” We might add “art history class,” or “art appreciation class.” What’s more, we could drop down from “art class” and create a set of species of “art class,” namely painting, drawing, or sculpting classes. Each time we move down from a genus term to a species of that term we increase the intension of the term and decrease its extension. There are more classes that can all be under “art class” than can fall under “painting.” “Art class” has a broader umbrella of classes, “painting” is more narrow.

The more we increase the intension and decrease the extension of a term, the more specific and concrete we get. “Painting class” is far more specific than “event.” And when it comes to terms as labels in a website organization structure, we always want to be as concrete as possible. Yet as we move up from a specific event listing to its event type, up again to its event category and finally back to the genus “event,” each step up requires an increase in the extension of our label terms, and thus a decrease in concreteness and specificity. And if we go too far up in order to encompass more species, we can lose so much intension that we become too vague or ambiguous to be meaningful and functional.

One of These Species Does Not Belong Here

Finding the right degree of extension and intension in our terms for clear, concrete, and functional organization is one skill that can help in the process of devising effective information architectures. Another skill is learning to keep your species straight. Often a species list gets invaded by strangers that do not belong. One way to make sure that each item in a species list is under one genus is to make sure that each item is mutually exclusive to the rest.

Mutually Exclusive Categories

Whenever you have a set of species of a particular genus term on the same level as one another, it’s critical that these terms be non-overlapping so they remain mutually exclusive. If you find a set of species under one genus and examples of one of the species could actually fit under some of the other species in the list, you have a problem.

Let’s take the genus term “bike” as an example. A list of species of the genus “bike” might include “bicycle,” “tricycle,” and “unicycle.” But can we add “recumbent bike” as a fourth? No. Because a recumbent bike can have two or three wheels, right? It could fall under more than one species (though a one wheel recumbent bike might be tricky). That’s because recumbent is a species of bicycle or tricycle, it is a subcategory, not a species of “bike” at the same level as “bicycle” or “tricycle.” Or another speciation problem comes from a mix of unlike terms: “bicycle,” “tricycle,” “unicycle,” “handlebar,” “pedal.” “Handlebar” and “pedal” don’t belong in this genus-species chart at all. They are not bikes. They are parts of a bike. These kinds of category mistakes are very common in website navigation hierarchies. Keeping the rules of genus-species relationships and thinking about the extension or intension of the terms you use for labels can help balance, organize, and build intuitive systems.

Defining Your Terms

In addition to using terms in proper relationship to each other, it’s important to make sure that terms are consistently defined. But this is very difficult when terms function as single word labels. The context of these terms on a museum website, and in relationship to one another in your menu, helps to define their meaning. But keep in mind that the broader a term is (the greater its extension), the more likely it is to become vague or ambiguous. You’ll need to make sure that you are being internally consistent in the use of your intended definition of your terms as you organize content under them.

Sometimes website labels are left deliberately vague with extreme degrees of extension, simply because you need a place to shove all the stuff that doesn’t neatly fit in a more concrete labeling system. “Explore” is often an example of a vague term whose definition is ambiguous, and can contain all sorts of content. Even worse is “Experience.” Often you can’t know what “Explore” might include until you explore it. And what kinds of content would be excluded from the label “Experience?” Categories like that, if we’re being ruthlessly honest, should be just be labeled “Surprise.”

Often labels like “Explore,” or “Learn,” or “Experience” become problematic not only because they have too much extension, but also because they fail the non-overlapping test. Can content listed as species under the label “Explore” also properly fit under other categories?

Using Nouns

One more useful rule of thumb that can help avoid ambiguous overlapping categories is the use of nouns rather than verbs in your labeling conventions. “Collection” is a noun that is very concrete and a visitor would know exactly what to expect there. “Explore” is a verb. And exploring is an activity that accompanies interaction with all kinds of content. Now sometimes, in order to simplify a menu, you may want to use some shorthand. So the term “Visit,” while it could be a verb or a noun, effectively functions as shorthand for “visitation information.” So even if your term can be ambiguously taken for a verb, always think of it as a noun when evaluating the species that properly belong under its genus.

Alternate Approaches: Audience-Based Navigation

When doing web strategy and content strategy, one part of our analysis is an evaluation of audiences. This is an important part of the process, and for museums, this is often a challenge, because who makes up the potential visiting audience for a museum? Well, who isn’t included? In a previous content strategy session with a museum client, in answer to the question “Who is your audience?” one participant said “humans.” And that’s very true. Nevertheless, we do have to think through specific constituencies such as educators, scholars, members of the media, and others who have specific expectations of the website.

Having worked through these perspectives it sometimes occurs to a group that perhaps they should organize their menus around these audience types. This is a bad idea. Organizing around audience types breaks the rules of mutual exclusivity. Can you really divvy up your content in such a way that each item belongs only to an educator, or a visitor, or a scholar, or a student? This structure inevitably breaks down and you begin to replicate and repeat content subcategories under each perspective. And then you have to have an entirely separate convention for content that is audience-neutral.

Additionally, if you are going to attempt to pre-filter, or sort your content based on what you think is of most interest to a particular audience, you’re most certainly going to make some incorrect assumptions. And besides, even when a teacher comes to the website, they come not only as a teacher, but also as an individual visitor, and as a curious human.

Instead, if your content is more objectively and concretely organized in an intuitive and consistent way, then all humans, regardless of their special interests, will be able to easily locate what is of most interest to them.

Specific Museum Conventions and Recommendations

As a specialist in museums, we’ve reviewed thousands of museum websites and built many ourselves. And in many ways, the main navigation systems are very similar. And this is a good thing. One error some museums make (one not limited to museums) is to want to get creative with labels. But getting creative comes at the high cost of inevitably introducing some degree of confusion or ambiguity. Back at the turn of the millennium, Steve Krug wrote one of the early books on website user experience called “Don’t Make Me Think.” This rule of thumb is basic to website navigation labels. If a term is well-worn, commonly used, and consistently in place, it’s a perfect candidate for use. You might tire of seeing it everywhere, but its ubiquity is a good thing. Getting creative only jettisons all of the common associations that make navigation intuitive. Go ahead and get creative with your content, not with the bones of your website’s skeletal system. Keep the hip bone connected to the leg bone, not the hip label connected to the vague association.

A museum website’s skeletal system should look like something like this:

Visit | Educate* (or Resources) | Collection(s) | Events | Stories | Support | About

With some exceptions and little alteration, this main menu would work for just about any museum. In terms of the specific definitions of these labels, “Visit” should be concrete information about hours, admissions, tickets, groups, accessibility, dining, and so forth.

*Educate (more often “Learn”) is always a questionable item. We like “Educate” better than “Learn” because it’s just a bit more concrete and is easily understood as shorthand for “Education,” a noun. “Learn” holds too tightly to its verby-ness. To a new visitor, “Learn” might not immediately mean “educator content.” And it’s also a bit of a problem related to the audience filtering issue. “Educate” might be better used as a subcategory or facet used in other areas of the site. “School tours” under “Visit” or “School Events” as a type of event, or “Educator content” as a filter to your collection objects.

In place of “Education” or “Learn” you might consider a “Resources” section, of which educator resources like lesson plans, or teaching programs might be found. Honestly, we’re even a bit uncomfortable with “Resources” due to the broad extension of that term. We’re still working on it.

The label “Collection” is as straightforward as you get–though it does often need to be subcategorized by various media, genre, or items on view. Also, rarely do museums have just one collection. Often there may be an archive, library, or living collection which are entirely different kinds of collections–so “Collections” plural is often a better label to encourage exploration.

“Events” or “Calendar” should lead to your main event listing or calendar page, with featured programs highlighted. (“Programs” is also a candidate for a main category, perhaps in place of “Resources” but there can be issues with the non-overlapping rule between “Events” and “Programs.” Those can sometimes be combined as one label “Events & Programs”).

We recommend a “Stories” label, particularly when we’ve helped clients craft an ongoing content strategy. A “Stories” section functions as an “amplified blog” whose posts can be used to augment other content through the website as well as in a serialized blog-like content stream.

“Support” (or “Join and Give”) is the place for all of your membership, donation, and volunteer information.

“About” is basic institutional information: Director’s welcome, leadership, staff, jobs, press, contact, etc.

We also recommend that “Contact” and “Search” be a part of your universal or utility navigation system and not include these in the main navigation bar. They are functional tools more than content categories, and people will find them easily enough if they need them.

It’s Not Rocket Science

Your museum’s information architecture should be simple, clear, and consistent. It should not reinvent the wheel. It’s not rocket science, but it should be informed by information science. The foundation of logic as applied to the science of terminology is a well-worn path. And the more you stay on these paths, you’ll not only be serving your website visitors, but your consistent use of these terms and categories will increase their effectiveness for all museums.